Canada

The Canadian government continues to scrutinize foreign investments by state-owned enterprises and state-linked private investors, especially if from "non-likeminded" countries.

Now a full decade in publication, White & Case's 2025 Foreign Direct Investment Reviews continues to provide a comprehensive look at foreign direct investment (FDI) laws and regulations across various countries and regions worldwide.

In this edition, we continue to offer key datapoints that can help inform parties and their advisors as they evaluate the new set of challenges presented by FDI screening requirements in cross-border transactions that span multiple countries.

FDI screening is continuously evolving, in fact, maturing. It is imperative to stay on top of the FDI requirements as transactions—be it mergers and acquisitions, investments, public equity offerings, or financial restructurings—are negotiated. Understanding the challenges, the potential remedies that could be required for approval and the proper allocation of FDI risk are key ingredients in avoiding unpleasant surprises related to timing, certainty and business plan execution.

With a new administration in the United States, a renewed US commitment to open foreign investment from allied countries, increased EU FDI cooperation, and the new geo-political lines and balances that are being drawn, the dynamics around FDI screening will be a driving consideration in the selection of investors in cross-border transactions. We continue to believe that most cross-border transactions will be successfully consummated in 2025, but understanding the evolving risks around FDI considerations will be critical.

The Canadian government continues to scrutinize foreign investments by state-owned enterprises and state-linked private investors, especially if from "non-likeminded" countries.

Foreign direct investments, whether undertaken directly or indirectly, are generally allowed without restrictions or without the need to obtain prior authorization from an administrative agency.

In the US, most FDI deals are approved without mitigation, but the landscape is evolving based on a combination of expanded jurisdiction and authorities, mandatory filings applying in certain cases, enhanced focus on a broad array of national security considerations, increased rates of mitigation, further attention to monitoring, compliance and enforcement, and a substantially increased pursuit of non-notified transactions.

The European Commission continues to be a driver of FDI screening across the EU, with Member States now moving toward coordinated enforcement.

The wide scope, low trigger thresholds and extensive interpretation of the Austrian FDI regime require a thorough assessment and proactive planning of the M&A process.

The Belgian FDI screening regime entered into force in July 2023. Investors and authorities alike are still coming to grips with the regime and the limited guidelines that help parties navigate it.

In 2024, Bulgaria established an FDI screening mechanism. Foreign investors' obligation to file for investment clearance did not become effective in 2024, but this should change soon.

The Czech Foreign Investments Screening Act took effect in May 2021, establishing the rights and duties of foreign investors and setting screening requirements for Czech targets.

The scope of the Danish FDI regime is comprehensive, and requires a careful assessment of investments and agreements involving Danish companies.

Estonia's FDI screening mechanism closed its first effective year in 2024.

FDI deals are generally not blocked in Finland, but the government is able to monitor and, if necessary, restrict foreign investment.

French FDI screening continues to focus on foreign investments involving medical and biotech activities, food security activities or the treatment, storage and transmission of sensitive data. The nuclear ecosystem is subject to very close scrutiny.

Following numerous amendments over the past years, Germany's FDI review continued in full swing in 2024, with further significant updates expected in the coming years.

State pre-emption right, excessively extended deadlines – significant changes in Hungarian FDI laws.

2025 summer update

Ireland's Screening of Third Country Transactions Act entered into force on January 6, 2025.

Italy's "Golden Power Law" review more tan ten years old and continuously expanding its reach.

The law in Latvia provides for sectoral FDI regimes for specific corporate M&A, real estate dealings and gambling companies.

All investments concerning national security are under the scope of review in Lithuania.

The Luxembourg FDI screening regime is now a year old, and the first notification filings have been made.

Malta's FDI regime regulates specific transactions that must be notified to the authorities and may potentially be subject to screening.

The Middle East continues to welcome foreign investment, subject to licensing approvals and ownership thresholds for certain business sectors or in certain geographical zones.

The Netherlands is set to expand its investment screening regime by extending the general mechanism to more sectors and by introducing additional sector-specific regulations.

Norway's foreign direct investment regime is in the process of being expanded, with more profound changes expected in the future.

After revision of the Polish FDI regime in 2024, the way the authorities are assessing transactions is evolving.

In Portugal, transactions involving acquisition of control over strategic assets by entities residing outside the EU or the EEA may be subject to FDI screening.

While far-reaching in its scope, compared to other EU countries, the Romanian FDI regime is generally perceived as investor-friendly.

The year 2024 was not marked by any major changes in the sphere of regulation of foreign investments in Russia, and the regulator continues to implement the course taken earlier in 2023.

After two years of foreign investment regulation in Slovakia, a supportive climate for foreign investments remains.

Slovenia's updated FDI regime now extends to branch offices and introduces new challenges for foreign investors navigating critical sectors.

Since 2020, certain foreign direct investments are subject to scrutiny in Spain and, since then, additional formalities have been introduced, specifically by a developing FDI regulation that entered into force on September 1, 2023. The FDI analysis is becoming increasingly crucial in the context of investments in Spain.

In its second year of operation, the Swedish FDI Act has become a standard component of a large portion of all transactions involving Swedish companies.

Apart from limited sector-specific regulations, there is currently no general FDI regime in Switzerland. An FDI Act is expected to come into force in 2026 at the earliest.

Strengthening Türkiye's position as a key investment hub remains a government priority.

Foreign direct investment is permissible in the UAE, subject to applicable licensing and ownership conditions.

FDI in the UK is covered by the National Security and Investment Act 2021, and in 2024 the government continued to update information and guidelines concerning the legislation.

Australia's FDI regimes underwent some modifications in 2024, designed to streamline the process of carrying out investments.

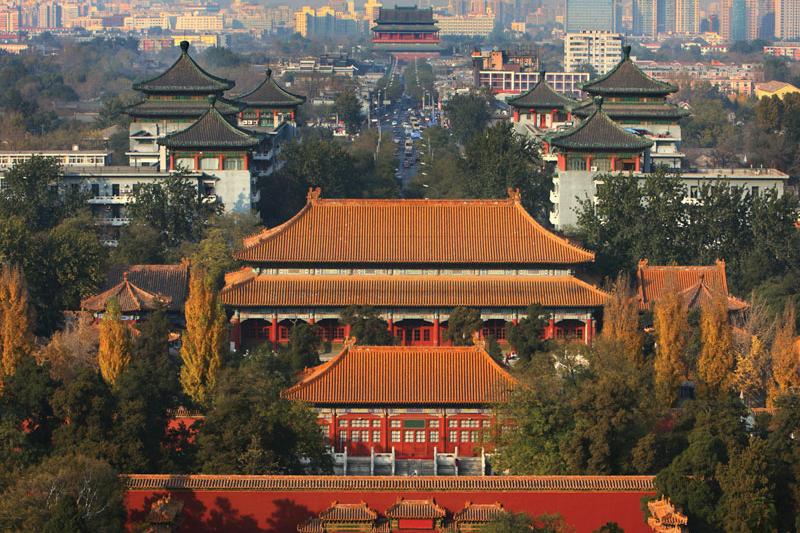

China continues to optimize its foreign investment environment by reducing investment restrictions, opening up market access and lowering investment thresholds into listed companies.

FDI continues to be an area of focus for the Indian government, which has announced plans to attract further foreign investment into the country.

The Japanese government expands business sectors subject to Japan's FDI regime to secure stable supply chains and mitigate the risk of technology leakage and diversion of commercial technologies into military use.

The Republic of Korea continues to welcome foreign investment, offering enhanced incentive packages and easing regulations while heightening scrutiny over transactions involving strategic industrial.

New Zealand has recently seen a period of stabilization of the overseas investment regime. However, following the formation of the coalition government at the end of 2023, this government has proposed significant changes to the overseas investment rules for 2025, making it easier for overseas investors to acquire New Zealand assets.

Taiwan continues to promote FDI under a two-track screening mechanism for foreign and PRC investors.

New Zealand has recently seen a period of stabilization of the overseas investment regime. However, following the formation of the coalition government at the end of 2023, this government has proposed significant changes to the overseas investment rules for 2025, making it easier for overseas investors to acquire New Zealand assets.

Explore Trendscape Our take on the interconnected global trends that are shaping the business climate for our clients.

Tessa Baker (Chapman Tripp) authored this publication.

The current regime is set out in the Overseas Investment Act 2005 (OIA) and is regulated by the Overseas Investment Office (OIO). Currently, the tenet of the regime is that it is a privilege for overseas persons to own or control sensitive New Zealand assets. Changes proposed to the OIA are anticipated to reverse this principle, with the starting assumption anticipated to be that the investment may proceed unless there is an identified risk to New Zealand's interests.

An overseas person making an acquisition that requires consent must apply to the OIO for that consent or clearance (as applicable) before completion of the acquisition. Any agreement for an acquisition must be subject to receiving such consent or clearance. The applicant is required to provide details of its structure, decision-making processes, details of how the investment will be funded, and controlling individuals; and for land applications, the benefits to New Zealand that would result from the investment.

An individual or entity will be considered an overseas person if they are not a New Zealand citizen, not ordinarily a resident of New Zealand, or in the case of an entity, incorporated overseas or more than 25 percent-owned or controlled by overseas persons. A New Zealand citizen or entity will also be considered an overseas person if they are investing on behalf of an overseas person.

A consent application includes a filing fee that varies according to the type and complexity of a transaction and whether a national interest assessment is required.

Consent under the OIA is required for a range of acquisitions by overseas persons, including an acquisition of a more than 25 percent ownership or control interest in a target entity—or an increase in an existing interest to or through 50 percent, 75 percent or 100 percent.

Consent is required where the value of the applicable New Zealand assets, or consideration attributable to those assets, exceeds NZD 100 million (or an alternative monetary threshold for investors from certain jurisdictions); or the target owns or controls, directly or indirectly, an interest in sensitive land. The definition of sensitive land is detailed and requires analysis from qualified advisors.

An overseas person, establishing a business in New Zealand must obtain consent if before commencing business, the expected expenditure incurred in establishing the business exceeds NZD 100 million (US$57.4 million), or the relevant alternative monetary threshold.

Direct acquisition of interests in sensitive land will also require consent, including the acquisition of a leasehold interest of three years or more for residential land, and ten years or more for other sensitive land, together with the acquisition of forestry rights and fishing quotas.

Consent requirements can be triggered for transactions occurring upstream of the New Zealand assets, as well as for direct acquisitions in New Zealand.

Investments in strategically important businesses, where a consent requirement is not already triggered, can, and in some cases must, be notified to the OIO for ministerial clearance. Mandatory notification is required for investments in critical direct suppliers to New Zealand's intelligence or security agencies and businesses involved in military or dual-use technology, but is otherwise optional. Non-notified transactions may be reviewed by the minister before or after completion of the investment.

Overseas investors and the controlling individuals are required to meet a bright-line investor test comprising a closed list of character and capability factors. This test applies whether the investment is in significant business assets, sensitive land, forestry rights or fishing quotas. Parties must wait until the assessment is complete and consent is granted before a transaction can be completed.

Examples of the investor test factors include whether the overseas investor has convictions resulting in imprisonment; corporate fines; prohibitions on being a director, promotor or manager of a company; penalties for tax avoidance or evasion; and unpaid tax of NZD 5 million or more in New Zealand or an equivalent amount in another jurisdiction.

Where the overseas investment is an investment in sensitive land, the overseas investor must also satisfy the benefit to New Zealand test. The requirements under the test differ depending on the nature of the land—for example, stricter provisions apply where the land is farmland. The OIO will assess the benefits that will be delivered by the transaction and consider factors including economic, environmental, public access, protection of historic heritage and advancement of government policy, and assess whether that benefit is proportionate to the sensitivity of the land and the nature of the transaction. A specific test must be met for investments in residential land—either increased housing, non-residential use or incidental residential use.

A national interest assessment applies to transactions involving strategically important businesses or being undertaken by foreign government investors. Supported by a cross-government committee, the minister has broad discretion to determine whether to block a transaction on the basis that it is contrary to New Zealand's national interests. The minister may address national security or public order risks by imposing conditions, prohibiting incomplete transactions, or requiring disposal if completion has already occurred.

Consent to a transaction is granted with standard conditions prescribed by the OIA and in many cases special conditions specific to the transaction. Investors are required to report to the OIO on progress in relation to the condition. If an overseas investor fails to comply with the conditions, the OIO can require the investment to be sold, and in cases of serious and deliberate breaches, criminal or civil penalties may be sought.

Timeframes under the regulations differ depending on the nature of the application. The statutory timeframe for a farmland application is 100 working days, while the timeframe for a business application is 35 working days. These timeframes can be paused or extended by the OIO. These timeframes do not create any legal obligation enforceable in a court of law, and there is no recourse for any applicant where the specified timeframe is not met. The 2024 Directive Letter has resulted in faster review timeframes.

Where the investment relates to a strategically important business, an initial review period of 15 working days applies, after which the OIO will inform the applicant of whether the transaction has been cleared or is being subjected to a more detailed assessment. If required, a full assessment must be completed within 55 working days.

In most circumstances, it is difficult to obtain consent under the OIA in advance of agreeing to a transaction, as the consent regime operates to screen specific transactions rather than simply to identify the investor. It is possible for an investor to apply on a standalone basis to be screened against the investor test, but this does not negate the need to seek consent for a relevant transaction, although in theory it would make that consent application easier and quicker.

Where consent under the OIA is required, or the investor is required or wishes to make a notification, the transaction should be conditional on receiving the relevant consent or clearance and must not proceed to completion until such consent or clearance is received.

Investors should assess early in a transaction process whether consent or notification under the OIA will be required. In some (but not most) circumstances, a discussion with the OIO ahead of filing can be helpful to gauge the OIO's reaction to aspects of the transaction.

Following a period of stability within the overseas investment regime in New Zealand, significant changes to New Zealand's overseas investment regime are expected in 2025. At the date of this article, exact details of these changes are yet to be announced, but it is expected that the rules will be relaxed to underpin the government's approach to overseas investment. This approach differs from past governments, as overseas investment is considered increasingly critical to New Zealand's economy, and attracting overseas investment is crucial in order for New Zealand to prosper.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2025 White & Case LLP