White & Case LLP has partnered with the Financial Times on the publication of its Moral Money Forum reports, which explore key issues from the ESG debate. This article has been reproduced with permission from the Financial Times.

In a choppy private fundraising environment, asset allocators to private markets face difficult choices. Does one stick to the path well-trodden by allocating capital to existing managers running classic fund strategies, or back emerging managers launching newer strategies with less rigorously tested theses? The tendency to minimise risk, has, however, not been enough to stymie the recent proliferation of impact funds in the market. Impact funds come in all shapes and guises, from maiden single-country focused sustainable forestry funds to buyout behemoth-sponsored global energy transition funds.

As asset allocators to private markets increasingly consider impact criteria in their own portfolio of fund investments, their discussions with sponsors are getting more detailed, and so are their contractual provisions in the fund documentation. A decade ago, investors seeking detailed criteria linked to tangible impact outcomes tended to be development finance institutions backing emerging managers, often in emerging markets. Larger, conventional institutional investors in private markets would have settled for the fund manager simply confirming that it had seen a copy of the investor's policies and commitments around sustainability and corporate social responsibility, or, at a push, that the fund manager was a signatory (or would otherwise have regard) to the UN Principles for Responsible Investment.

The market has come a long way from the nebulous commitments of managers to monitor ESG improvements in their portfolio investments. Impact funds are demonstrating that creating and/or contributing to positive social or environmental outcomes through portfolio investments is not at odds with aspiring to, and achieving, financial returns commensurate with more traditional private funds. Of course, in an industry that has been reluctant for decades to move away from the traditional "two and twenty" model, it is hardly surprising that only a small minority of managers are willing to embed impact-linked metrics on calculation of carried interest or performance-based fees.

More frequently, we see fund managers retaining dedicated impact specialists (usually engaged by the manager centrally and deployed across all relevant fund products) to provide investors with additional comfort regarding the approach to investment diligence and ongoing operation. Special governance measures are also increasingly being introduced such as a dedicated ESG subcommittee of the investor advisory committee that will have relevant matters for consideration and approval referred to them. In part, this is attributable to the lack of uniform standards and metrics for assessing impact outcomes.

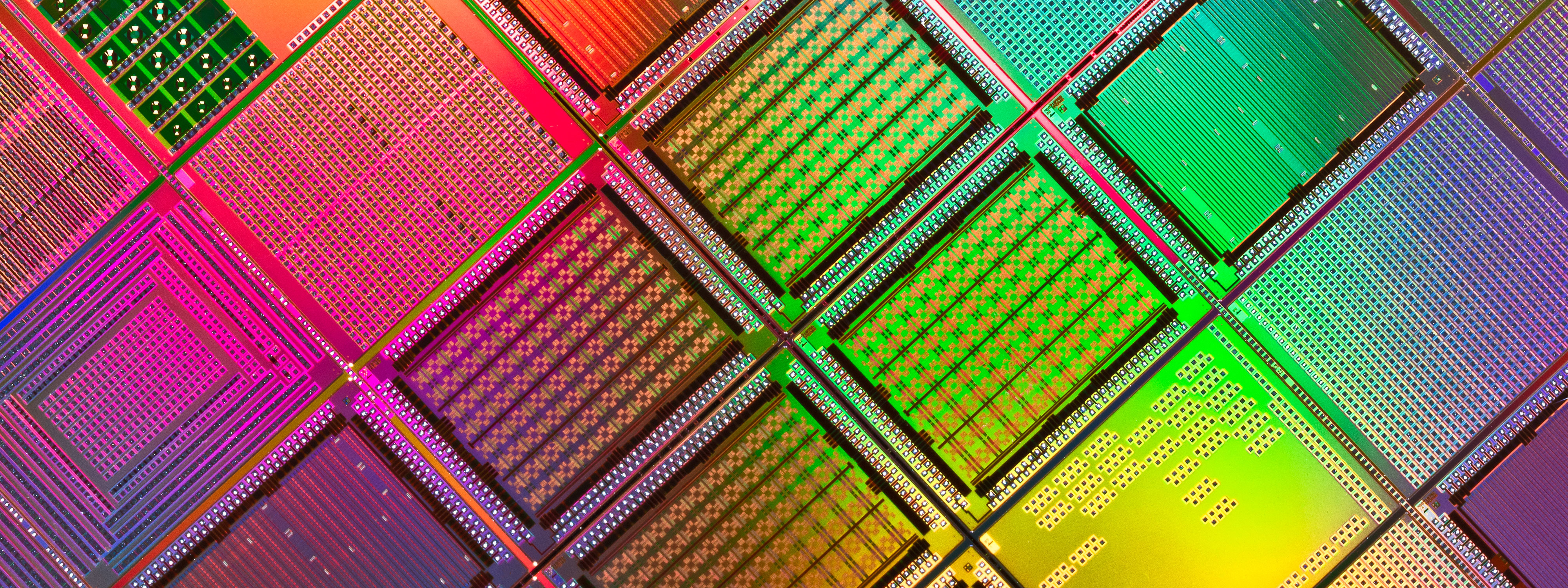

To begin with, there is no definition of impact investing that has been universally adopted by private market sponsors or investors. For example, a strategy that focuses on investments in technology venture capital companies in emerging markets would not traditionally have been viewed as an obvious proposition through an ESG lens, but from a wider impact perspective, shows tremendous potential for sector disruption. Such disruption could lead to a positive social or environmental impact through, for example, financial inclusion, or the development of blockchain solutions which could deliver more sustainable infrastructure. Strategies would also need to take account of potentially negative social or environmental impact such as distributed ledger technology facilitating financial crime, or blockchain validation processes requiring excessive energy consumption and electronic hazardous waste.

The importance of impact investing is not only rising in the context of primary investments (when the fund is open to new investors) but has recently also permeated the burgeoning secondaries market, comprising transfers of existing fund interests, fund restructurings and other transactions aimed at providing liquidity to investors. In traditional secondary transactions, investors acquire fund interests from existing investors, to gain exposure to identified companies held by a given fund. Because of the stage of the fund's life in which secondaries investors enter the fray, there is often no room for such investors to negotiate forward-looking side letters (being bilateral agreements between the fund and the investor covering a range of issues on which the investor seeks more specific contractual comfort, from ESG to economic entitlements).

Therefore, more emphasis is placed on the due diligence of the actual assets that have been acquired by the fund and, for the impact-minded investor, making sure the strategy meets certain key performance indicators. This can help mitigate the risk of investors being accused of greenwashing, or being faced with regulatory enforcement risk in view of the anticipated substantial evolution (particularly in Europe) of sustainable finance disclosure rules, such as the relevant regulatory technical standards and published guidance with respect to the EU's Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR). Despite expected changes to the SFDR regime, national authorities indicate that they will ramp up enforcement in its present form, in connection with existing practices.

Secondaries investors are increasingly scrutinising existing or contemplated impact investing strategies, with several of the larger investors having recently launched dedicated secondaries impact teams that focus on delivering market rate returns. Impact investors' emphasis on market rate returns has been seen in the purchase and sale agreements for these secondary fund interests exposed to portfolio companies engaged in delivering impact outcomes. Such agreements usually include a purchase price that reflects a discount to the fund's reported valuation, as agreed between the seller (the existing investor) and the buyer. Of note, the discount for impact investing portfolios tends to be steeper than traditional buyout fund interests (in the order of 30 to 50 per cent), given the higher risk associated with these strategies. The pricing itself is an indication that impact investors are seeking to derive a financial return in addition to promoting systemic change.

This publication is provided for your convenience and does not constitute legal advice. This publication is protected by copyright.