Long awaited EU AI Act becomes law after publication in the EU’s Official Journal

11 min read

On 12 July 2024, the European Union's Artificial Intelligence Act, Regulation (EU) 2024/1689 ("EU AI Act") was published in the EU Official Journal, making it the first comprehensive horizontal legal framework for the regulation of AI systems across the EU. The EU AI Act enters into force across all 27 EU Member States on 1 August 2024, and the enforcement of the majority of its provisions will commence on 2 August 2026.

Overview

The EU AI Act is a result of extensive negotiation, aimed at laying down a harmonised legal framework "for the development, the placing on the market, the putting into service and the use of artificial intelligence systems" in the EU. Spanning 180 recitals and 113 Articles, the new law takes a risk-based approach to regulating the entire lifecycle of different types of AI systems. Non-compliance with the EU AI Act will be met with a maximum financial penalty of up to EUR 35 million or 7 percent of worldwide annual turnover, whichever is higher.

Scope of Application (Art. 3(1) EU AI Act)

In order to distinguish AI from simpler software systems, Art. 3(1) EU AI Act defines an AI system as "a machine-based system that is designed to operate with varying levels of autonomy and that may exhibit adaptiveness after deployment, and that, for explicit or implicit objectives, infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs such as predictions, content, recommendations, or decisions that can influence physical or virtual environments". This definition is aligned with the definition provided by the OECD to the term.1

The EU AI Act establishes obligations for providers, deployers, importers, distributors, and product manufacturers of AI systems, with a link to the EU market. For example, the EU AI Act applies to: (i) providers which place on the EU market or put into service AI systems, or place on the EU market general-purpose AI models ("GPAI models"); (ii) deployers of AI systems who have a place of establishment/are located in the EU; and (iii) providers and deployers of AI systems in third countries, if the output produced by the AI system is being used in the EU (Art. 2(1) EU AI Act). The EU AI Act also enumerates certain exceptions to its material scope (for example, the EU AI Act does not apply to open-source AI systems unless they are prohibited or classified as high-risk AI systems or AI systems used for the sole purpose of scientific research and development) (Arts. 2(3), 2(4), 2(6), 2(8), 2(10) and 2(12)).

Member States are able to maintain or introduce regulations that are more favourable to workers in terms of protecting their rights in respect of the use of AI systems by employers, or encouraging or allowing the application of worker-friendly collective agreements (Art. 2(11) EU AI Act).

Prohibited AI Systems (Art. 5 EU AI Act)

The EU AI Act bans certain AI practices across the EU, which it considers harmful, abusive and in contradiction with EU values. The prohibited AI practices include the deployment of subliminal AI techniques beyond a person's consciousness or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques, with the objective, or the effect of, materially distorting human behaviour.

It, however, provides for a few exceptions to this rule for law enforcement purposes relating to the use of 'real time' remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces (Art. 5(2) EU AI Act).

High-risk AI Systems (Chapter III EU AI Act)

With the aim of implementing a proportionate and effective set of rules for AI systems, the EU AI Act establishes a risk-based approach to regulation and categorises AI systems based on the intensity and scope of the risks each AI system can generate. "High-risk AI Systems", which are systems that present a "high" risk, fall within two categories: (i) AI systems used as a safety component of a product (or otherwise subject to EU health and safety harmonisation legislation); and (ii) AI systems deployed in eight specific areas, including (among others) education, employment, access to essential public and private services, law enforcement, migration, and the administration of justice (Art. 6(1)-(2) and Annex III EU AI Act). As a derogation, an AI system that falls within those eight specific areas may be deemed as not posing a high such risk if its intended use is limited to:

- Performing narrow procedural tasks

- Making improvements to the results of previously completed human activities

- Detecting decision-making patterns or deviations from prior decision-making patterns without replacing or influencing human assessments

- Mere preparatory tasks to a risk-assessment, (Art. 6(3) EU AI Act)

However, for clarity, an AI system deployed in the eight specified areas is always considered high-risk if it performs profiling of natural persons (Art. 6(3) EU AI Act).

The EU AI Act imposes a wide range of obligations on the various actors in the lifecycle of a high-risk AI system, which include requirements on data training and data governance, technical documentation, recordkeeping, technical robustness, transparency, human oversight, and cybersecurity. For example, high-risk AI systems which make use of techniques involving the training of models with data will have to be developed on the basis of training, validation and testing data sets that meet the quality criteria set by Art. 10 EU AI Act. The EU AI Act also provides for a process and criteria for the addition of new or the modification of existing use cases for high-risk AI systems by the EU Commission (Art. 7 EU AI Act).

GPAI Models (Chapter V EU AI Act)

The EU AI Act sets out a dedicated chapter for the classification and regulation of GPAI models. A GPAI model is defined as "an AI model, including where such an AI model is trained with a large amount of data using self-supervision at scale, that displays significant generality and is capable of competently performing a wide range of distinct tasks regardless of the way the model is placed on the market and that can be integrated into a variety of downstream systems or applications, except AI models that are used for research, development or prototyping activities before they are placed on the market" (Art. 3(1)(63) EU AI Act). It remains to be seen how competent regulators and courts will interpret the definition (in particular, what "significant generality" means).

As noted above, the EU AI Act will not apply to any AI systems or models (including GPAI models and their output) where they are specifically developed and put into service for the sole purpose of scientific research and development (Art. 2(6) EU AI Act).

The classification of GPAI models with systemic risk is addressed in Art. 51 EU AI Act. A GPAI model is classified as a GPAI model with systemic risk if it has high impact capabilities (evaluated on the basis of appropriate technical tools and methodologies, including indicators and benchmarks) or is identified as such by the Commission. A GPAI model is presumed to have high impact capabilities2 if the amount of computational power, measured in floating point operations (FLOPs), is greater than 1025 (Art. 51(2) EU AI Act).

The provider of a GPAI model is required to notify the Commission if they become aware that a GPAI model does or will qualify as one with systemic risk without delay, and in any event within two weeks (Art. 52(1) EU AI Act). A list of AI models with systemic risk will be published and frequently updated by the Commission, without prejudice to the need to observe and protect intellectual property rights and confidential commercial information or business secrets in accordance with EU / Member State law (Art 52(6) EU AI Act).

All providers of GPAI models are subject to certain obligations, such as: (i) making available and maintaining up-to-date technical documentation, including its training and testing process, or providing information to AI system providers who intend to use the GPAI model; (ii) cooperating with the Commission and national competent authorities; and (iii) respecting national laws on copyright and related rights (Art. 53 EU AI Act). Providers of GPAI models with systemic risk have additional obligations, including the obligations to perform standardised model evaluations, assess and mitigate systemic risks, track and report incidents and ensure cybersecurity protection (Art. 55 EU AI Act).

The EU AI Act directs the EU's AI Office to encourage and facilitate the drawing up of codes of practice at the EU level to "contribute to the proper application" of the law, taking into account "international approaches" (Art. 56 EU AI Act). The EU AI Act envisages that the codes of practice will represent a "central tool" for the proper compliance by providers of GPAI models with the relevant obligations provided for under the EU AI Act.3 Providers of GPAI models may rely on codes of practice (within the meaning of Art. 56 EU AI Act) to demonstrate compliance with the obligations imposed on all providers of GPAI models under the Act, until a harmonised standard is published. Providers of GPAI models will need to be able to demonstrate compliance using alternative adequate means, if codes of practice or harmonised standards are not available, or if they choose not to rely on those.

Deep fakes (Art. 50 EU AI Act)

Deep fakes are defined as "AI-generated or manipulated image, audio or video content that resembles existing persons, objects, places, entities or events and would falsely appear to a person to be authentic or truthful" (Art. 3(60) EU AI Act).

Under the EU AI Act, deployers who use AI systems to create deep fakes are required to clearly disclose that the content has been artificially created or manipulated by labelling the AI output as such and disclosing its artificial origin (unless the use is authorised by law to detect, prevent, investigate, and prosecute a criminal offence). Where the content forms part of evidently artistic work, the transparency obligations are limited to disclosure of the existence of such generated or manipulated content in a way that does not hamper the display or enjoyment of the work (Art. 50(4) EU AI Act).

Penalties (Chapter XII EU AI Act)

The maximum penalty for non-compliance with the EU AI Act's rules on prohibited uses of AI is the higher of an administrative fine of up to EUR 35 million or 7 percent of worldwide annual turnover (Art. 99(3) EU AI Act). Penalties for breaches of certain other provisions4 are subject to a maximum fine of EUR 15 million or 3 percent of worldwide annual turnover, whichever is higher. The maximum penalty for the provision of incorrect, incomplete, or misleading information to notified bodies or national competent authorities is EUR 7.5 million or 1 percent of worldwide annual turnover, whichever is the higher (Art. 99(5) EU AI Act). For SMEs and start-ups, the fines for all the above are subject to the same maximum percentages or amounts, but whichever is lower (Art. 99(6) EU AI Act).

There is also a penalty regime for providers of GPAI models, set out in Art. 101 EU AI Act, which provides that providers of GPAI models may be subject to maximum fines of 3 percent of their annual worldwide turnover or EUR 15 million, whichever is higher. Fines will be imposed if the Commission finds that the provider intentionally or negligently infringed the relevant provisions of the EU AI Act, failed to comply with a request for documentation or information (or supplied incorrect, incomplete or misleading information), failed to respond to requests from the Commission made pursuant to Art. 93 EU AI Act, or failed to provide the Commission with access to the GPAI model for the purpose of conducting an evaluation.

The EU AI Act also stipulates the rights of natural and legal persons to lodge a complaint with a market surveillance authority, to explain individual decision-making, and to report instances of non-compliance under Arts. 85 – 87.

Member States are required to take into account the interests of SMEs, including start-ups, and their economic viability, when introducing penalty levels for violations of the EU AI Act (Art. 99(1) EU AI Act).

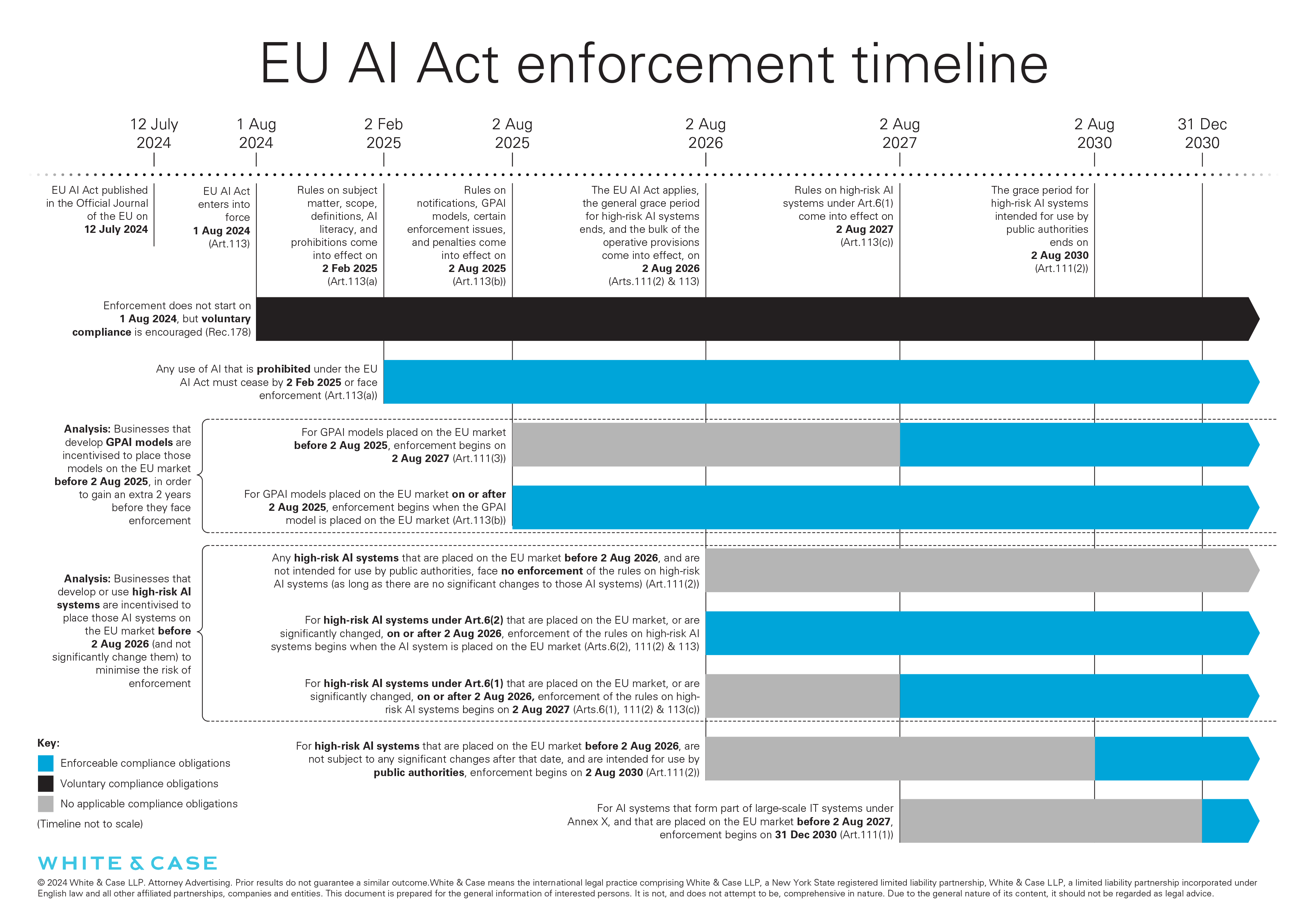

Implementation timeline (Art. 113 EU AI Act)

The EU AI Act enters into force on 1 August 2024, which is the 20th day after its publication in the EU Official Journal. The EU AI Act will be effective from 2 August 2026 (Art. 113 EU AI Act), except for the following specific provisions listed in Art. 113(a)-(c) EU AI Act:

(a) Enforcement of Chapters I and II (general provisions, definitions, and rules regarding prohibited uses of AI) starts from 2 February 2025 (Art. 113(a) EU AI Act)

(b) Enforcement of certain requirements (including notification obligations, governance, rules on GPAI models, confidentiality, and penalties (other than penalties for providers of GPAI models)) starts from 2 August 2025 (Art. 113(b) EU AI Act). However, providers of GPAI models placed on the EU market before 2 August 2025 get until 2 August 2027 to achieve compliance (Art. 111(3) EU AI Act)

(c) Enforcement of Art. 6 (and the corresponding obligations regarding high-risk AI systems) starts from 2 August 2027 (Art. 113(c) EU AI Act)

Until the relevant provisions of the EU AI Act come into force, providers of high-risk AI systems are encouraged to comply on a voluntary basis (Rec. 178 EU AI Act).

Member States will have to: (i) designate at least one notifying authority and one market surveillance authority; and (ii) communicate to the Commission the identity of the competent authorities and the single point of contact. They also will have to make publicly available information on how competent authorities and single point of contact can be contacted by 2 August 2025 (Art. 70(2) EU AI Act).

Each Member State is required to establish at least one operational regulatory sandbox at the national level by 2 August 2026 (Art. 57(1) EU AI Act).

1 See OECD Recommendation on Artificial Intelligence 2019.

2 Defined in Art. 3(64) EU AI Act as "capabilities that match or exceed the capabilities recorded in the most advanced [GPAI models]".

3 See Recital 117 of the EU AI Act.

4 See provisions laid down in Art. 99 (4) EU AI Act.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2024 White & Case LLP

View full image: EU AI Act enforcement timeline (PDF)

View full image: EU AI Act enforcement timeline (PDF)