NAV and holdco back-levering financings – practicalities of collateral enforcement by asset class

23 min read

The structures for net asset value ("NAV") financings and what we might call "NAV-adjacent transactions" – i.e. holdco or aggregator financings over a single or limited number of portfolio investments with credit support provided by the investment fund – are as varied as the investment funds and portfolio investments they finance. As a result, the types and scope of collateral available to be pledged to a NAV lender will vary widely across transactions, and it is incumbent on lenders and their counsel to understand the collateral being taken in each transaction, the options available to the lender for enforcement of that security and the rights to be obtained upon enforcement.

In this chapter, we will explore some of the most common issues that arise in structuring a NAV collateral package and understanding the lenders' path to enforcement.

Chapters in previous editions of this book, including our own,1 have chronicled the rise of the NAV lending market in the fund finance space and the structures these facilities adopt. Set out below is a brief explanation of the most common collateral structures and enforcement mechanics.

Credit fund NAVs

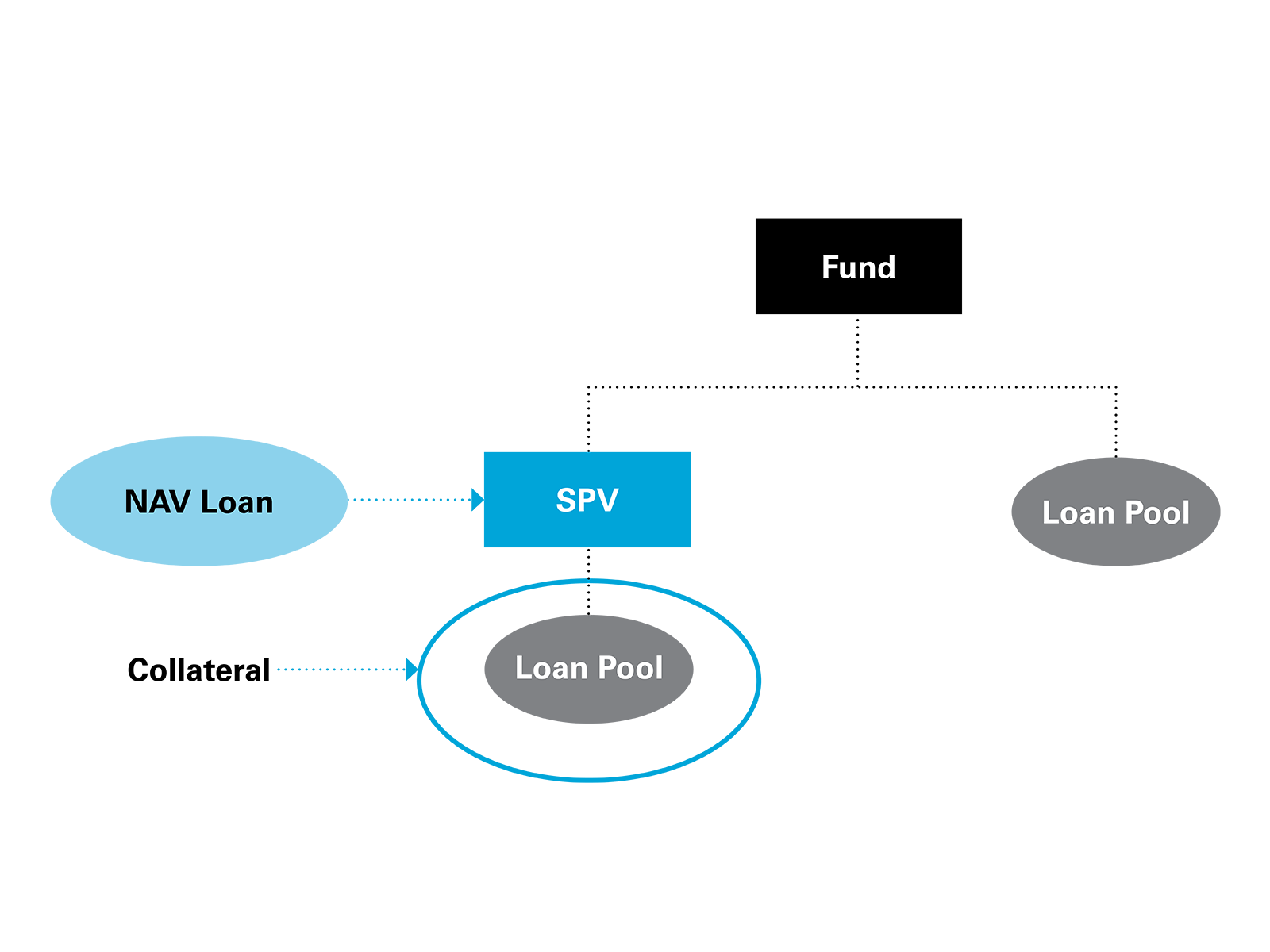

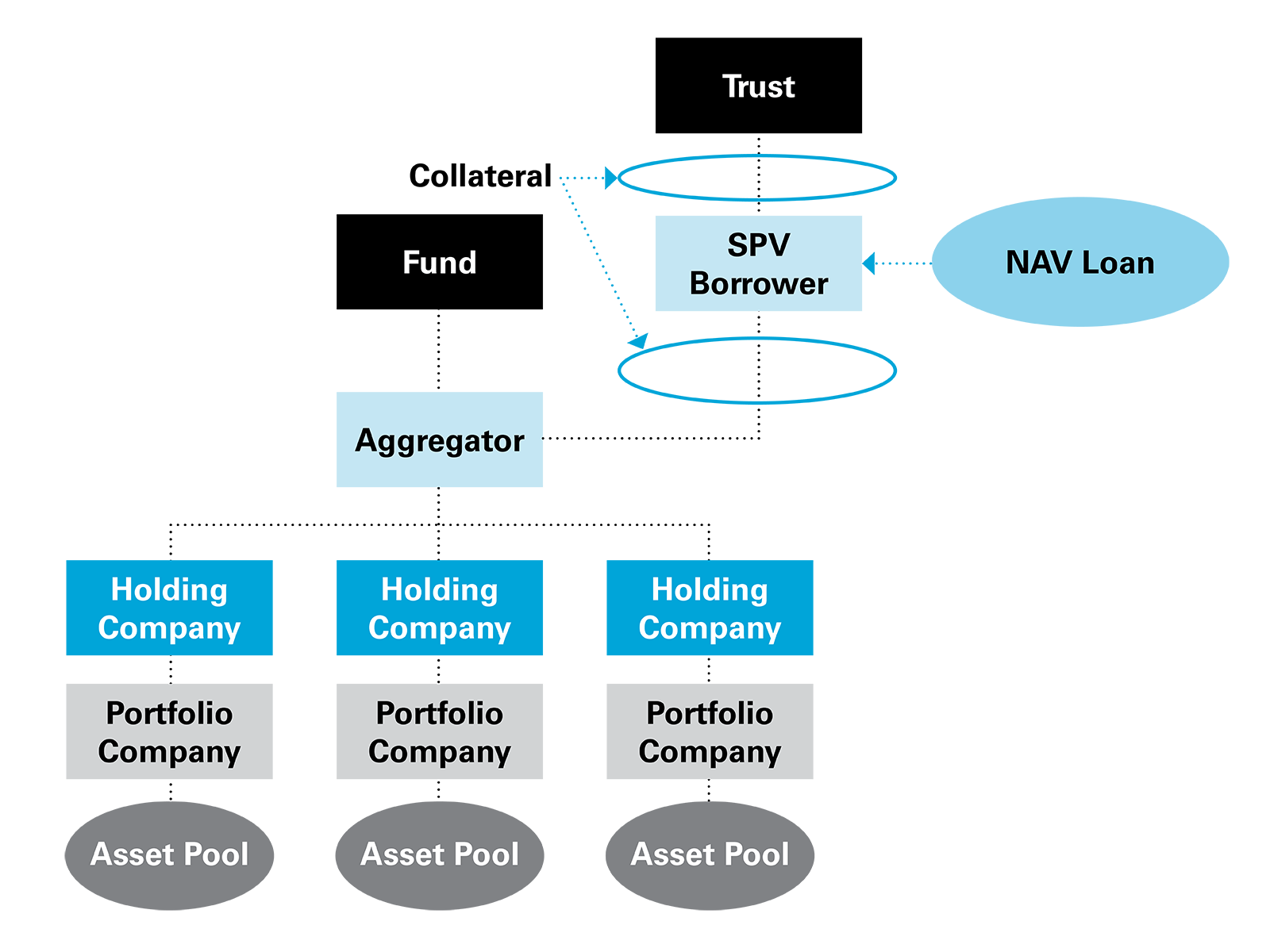

Perhaps the seemingly simplest structure for a NAV facility is one commonly used by credit funds. In this structure, the credit fund holds a portfolio of loans that it has accumulated over time, often using financing from a subscription line or other revolving warehouse facility at the fund level. The fund assigns the loans that are to be financed by the NAV facility into a newly formed special purpose vehicle ("SPV"). That SPV becomes the borrower under the NAV facility and pledges the loans it holds to the lenders as security for the NAV facility, together with the bank account(s) into which payments on the loans are to be paid (see fig. 1). These NAV facilities are typically non-recourse to the fund (i.e. if the returns from the loan portfolio and/or any proceeds on enforcement are insufficient to repay the NAV facility in full, the NAV lenders cannot pursue the fund for payment of any deficiency). Consequently, to further protect the interests of the lenders, the SPV is most often required to be bankruptcy remote, including having at least one independent director, and to structure itself in a manner designed to avoid the risk of substantive consolidation with the fund in the event of a fund insolvency. These provisions are most often found in the organisational documents of the SPV but can also be included as covenants in the NAV facility agreement.

A variety of loan types may be included in a credit fund NAV financing. The NAV facility generally utilises a borrowing base approach to determining the amount of credit available based on any given loan portfolio – much like asset-based lending ("ABL") facilities common for commercial enterprises. The advance rate for individual loans is a function both of their credit quality and ease of enforcement. Higher quality, liquid assets that can be sold easily on enforcement (such as syndicated "term loan Bs") receive a higher advance rate than lower quality and/or less liquid assets (such as second lien loans, mezzanine loans and direct lending assets) that may be more difficult for the lender to dispose of. Over time, a credit fund may enter into multiple NAV facilities involving separate SPVs. This might be simply a function of time, with loans being dropped into an SPV and financed via a NAV as and when sufficient loans have been accumulated, or separate SPVs could be used to pool together loans with similar credit characteristics in specialised financings.

As noted above, the collateral for a credit fund NAV is a pledge of the loans in the portfolio as well as the bank accounts into which payments are received. Because the NAV lender has a direct pledge of the loans, enforcement is a relatively straightforward process of selling the loans in the secondary market. For syndicated loans, this follows the usual process for assignments pursuant to the relevant loan agreements and customary secondary market trading practices. For loans that are not syndicated, the NAV lender will need to be cognisant of the terms of each relevant loan agreement in order to transfer the loans on enforcement. This may mean obtaining the consent of a third-party administrative agent and/or the borrower under the loan and navigating a hodgepodge of "disqualified lender" definitions and other transfer restrictions that will need to be addressed on a loan-by-loan basis. For a portfolio with perhaps hundreds of such loans, the enforcement process can be quite cumbersome.

For the same reason, while this structure appears simple, it is not necessarily the fastest or cheapest to effectuate. This is because the same loan agreement provisions that govern the lender's ability to transfer the loans on enforcement also govern the fund's ability to transfer them into the SPV. In many cases, the underlying loan agreements will permit the fund, as the lender, to transfer the loans to affiliates free of any agent or borrower consent requirements. Where that is the case, the loan can be transferred to the SPV without the need for third-party consent, but it is incumbent on the credit fund to review each loan agreement to ensure it is complying with the relevant provisions, and on the NAV lender and its counsel to ensure that title to each relevant loan is validly transferred to the SPV.

It should also be noted that the NAV facility security will be governed by the law provided for in the NAV security documents. This will often be New York ("NY") law for NY law-governed NAV facilities, but may include a variety of other jurisdictions where local law dictates that pledges of receivables be governed by the jurisdiction in which the pledgor is located. Transfers of the underlying pledged loans, by contrast, will be governed by the governing law of their respective loan agreements. As a result, the NAV lender may find that while one jurisdiction's law governs its ability to enforce its pledge and obtain control of a loan vis-à-vis the NAV borrower, another jurisdiction's law may govern any transfer of that loan to a third party. Careful attention should be paid to these governing law provisions and the enforcement mechanics available under the laws of the relevant jurisdictions at the outset of the NAV financing to ensure the lender understands and is signed off on the available path(s) to enforcement.

Figure 1:

Secondary fund NAVs

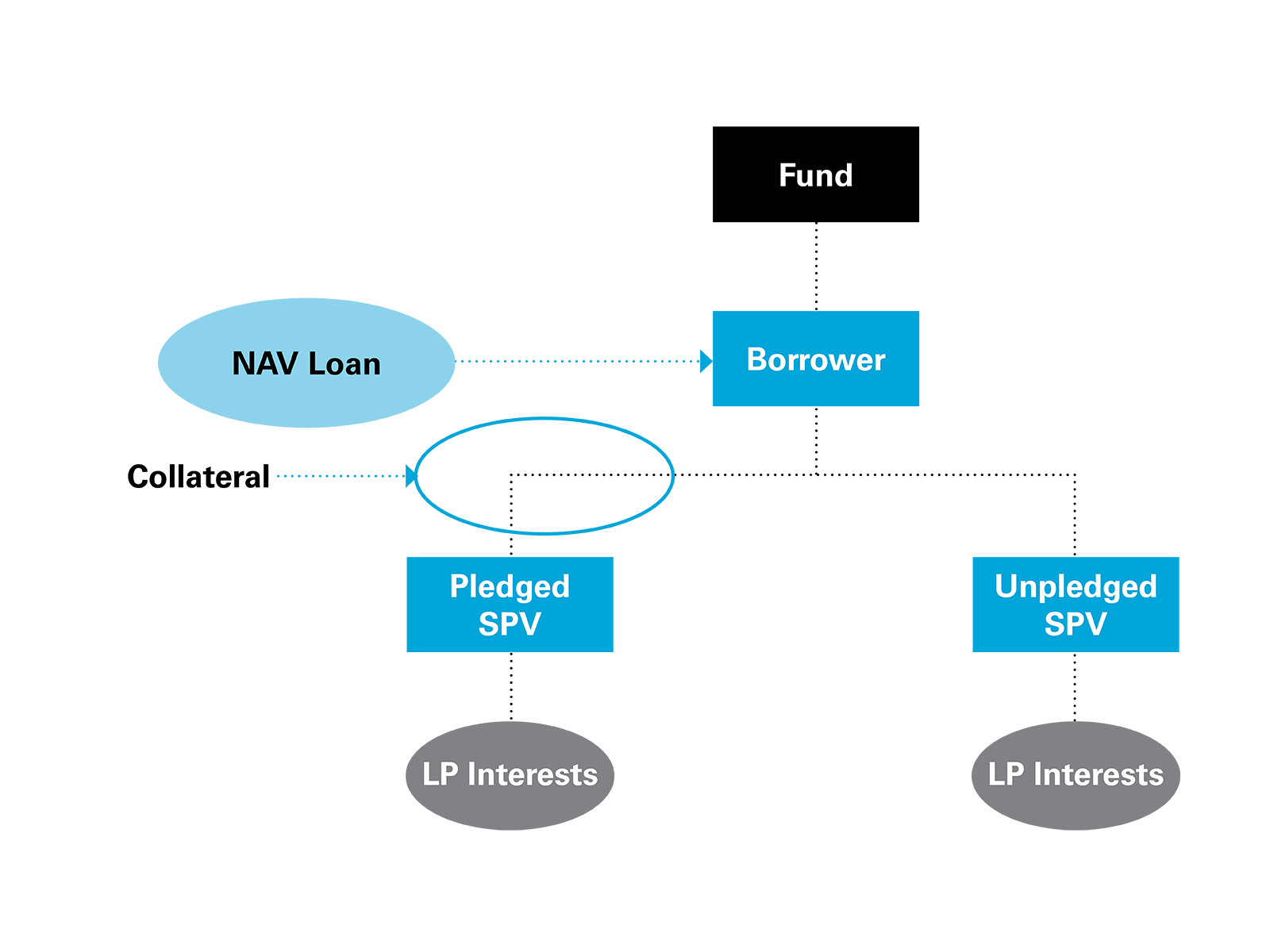

Secondaries funds are funds that hold portfolios of limited partnership ("LP") interests in other funds, often acquired in a mixture of single-asset and portfolio acquisitions. When structuring a NAV facility for a secondaries fund, the borrower will most often be an aggregator vehicle one or two levels below the actual fund. The NAV borrower will hold the underlying portfolio of LP interests through one or two SPVs, much like we saw with credit funds. However, the purpose of the SPVs here is different. In the case of secondaries funds, the limited partnership agreements ("LPAs") governing the LP interests in the portfolio virtually always require consent of the general partner ("GP") of the underlying fund in order for a limited partner to transfer its LP interest, including via a pledge. Thus, holding the LP interests in an SPV and pledging the equity of the SPV avoids a direct pledge of the LP interests and, in most cases, avoids triggering the GP consent requirements.

There will be some cases, however, in which even the pledge of the equity of the SPV would be subject to the underlying LPA consent requirements. In those cases, the LPA will contain "indirect" transfer restrictions that pick up not only a direct pledge or other transfer of the LP interest itself, but also a pledge or other transfer of the equity of the relevant limited partner – i.e. a change of control of the limited partner. To ensure that the NAV facility does not run afoul of these indirect transfer restrictions, the most common solution is to bifurcate the portfolio of LP interests such that those LP interests that are subject to indirect transfer provisions are held by one SPV and the remainder (in most cases, the majority) are held by a second SPV. Only the equity of the second SPV is pledged as collateral for the NAV facility (see fig. 2).

Importantly, in addition to the pledge of the equity of the SPV holding the "pledged LP interests", the NAV borrower also pledges its bank accounts into which all proceeds flowing upwards from the portfolio are deposited. This ensures that, although the NAV lender does not have security over the "unpledged LP interests", it nevertheless obtains security over any proceeds of those interests that are paid up to the NAV borrower and deposited to its bank accounts.

Upon enforcement of the NAV facility security, the NAV lender is able to foreclose on the equity of the pledged SPV and, by obtaining control of that entity, to direct the disposition of the underlying portfolio of LP interests. As with portfolios of credit fund assets, those dispositions are subject to the GP consent requirements and other transfer restrictions in the relevant LPAs, but the disposition of a portfolio by a NAV lender in this manner is fundamentally no different than any other sale of LP interests in the secondary market. The NAV lender is not able to obtain control of the unpledged SPV or its assets, but continues to benefit from any proceeds of those assets as and when they are paid into the NAV borrower's bank accounts.

Like with credit funds, paying attention to the relevant laws governing enforcement will be critical. The pledge of the equity of the pledged SPV will typically be governed by the law of its jurisdiction of organisation or, in the case of a Delaware entity, by NY law. Depending on the fund structure and tax characteristics, these SPVs are most likely to be formed in Delaware, the Cayman Islands, Luxembourg or other common fund domiciles, all of which generally permit enforcement of equity pledges via out-of-court procedures. Once the NAV lender has obtained control of the NAV borrower following enforcement of its equity pledge, dispositions of the LP interests held by the SPV will be governed by the governing law of their respective LPAs. Consequently, as with credit funds, the NAV lender may find that one jurisdiction's law governs its ability to enforce its pledge and obtain control of the SPV and a multitude of other laws (albeit also a mixture of the same common fund domiciles) govern disposal of the portfolio assets.

Figure 2:

Private equity and infrastructure NAV with direct security

As we move into the world of private equity ("PE") and infrastructure funds, the challenges of structuring a collateral package acceptable to NAV lenders increase. This is due to a number of factors.

First, PE and similar assets will have their own portfolio company leverage facilities in place, with each portfolio company and its respective assets being pledged to secure the operating company debt. The loan documents for those loans will include change of control provisions that would require repayment of the loans should a change of control occur. For a NAV lender, this means that, regardless of the validity and perfection of its security interest over the NAV facility collateral, actually enforcing that collateral could result in a value-destroying free-for-all at the portfolio company level. How a change of control is defined in each of the operating company loan agreements will thus be important to ascertain in order to understand how the NAV facility collateral package or any potential enforcement may impact the portfolio.

Secondly, the nature of the underlying portfolio investments may also impact the ability of a lender to take a pledge of the equity of a NAV borrower or its interest in an investment holding company. If the underlying portfolio company is in a regulated industry such as insurance, financial institutions, energy, telecoms, etc., a transfer of a controlling interest, whether directly or indirectly, may involve a lengthy regulatory approval process. In most cases, these provisions will apply only if and when the lender seeks to transfer the equity interest in foreclosure. There are instances, however, where regulatory consents are required for the pledge itself.

Another issue that must be considered is to what extent a pledge of the equity of the NAV borrower or an aggregator vehicle will conflict with other transfer restrictions further down the corporate chain of one or more portfolio companies. These may include, for example, consent requirements, rights of first refusal, tag-along rights and similar provisions included in shareholders' agreements entered into with co-investors or management of a portfolio company and/or provisions that would trigger a MOIC ("multiple on invested capital") requiring that such co-investors or management receive a minimum return should the fund exit an investment within a stated period. Understanding and accounting for the economic and practical impact of these provisions on a potential NAV enforcement are important to ensuring the NAV lender has an accurate picture of its path to enforcement and any detractions from the value to be obtained on enforcement.

Finally, the cost of taking the desired security should be considered. In most cases, a pledge of the holding company at the top of each portfolio company asset silo will be governed by the law of the jurisdiction of formation of the pledged entity. Depending on the number of companies and jurisdictions involved and the relevant local law requirements in those jurisdictions, taking security over a large portfolio of diverse global assets can quickly become a time-consuming and expensive exercise. Enforcement of these pledges will be subject to the same governing law considerations discussed above.

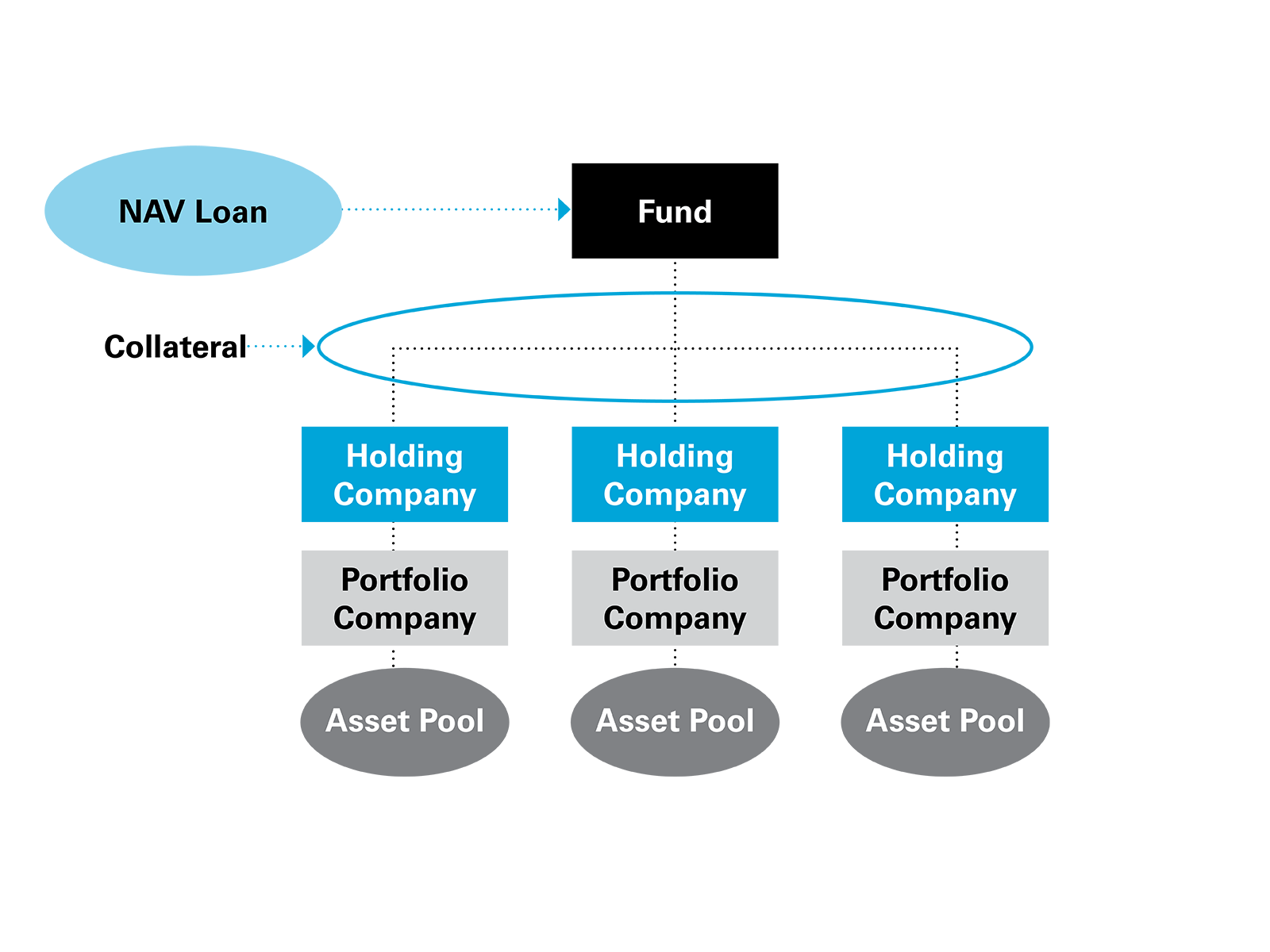

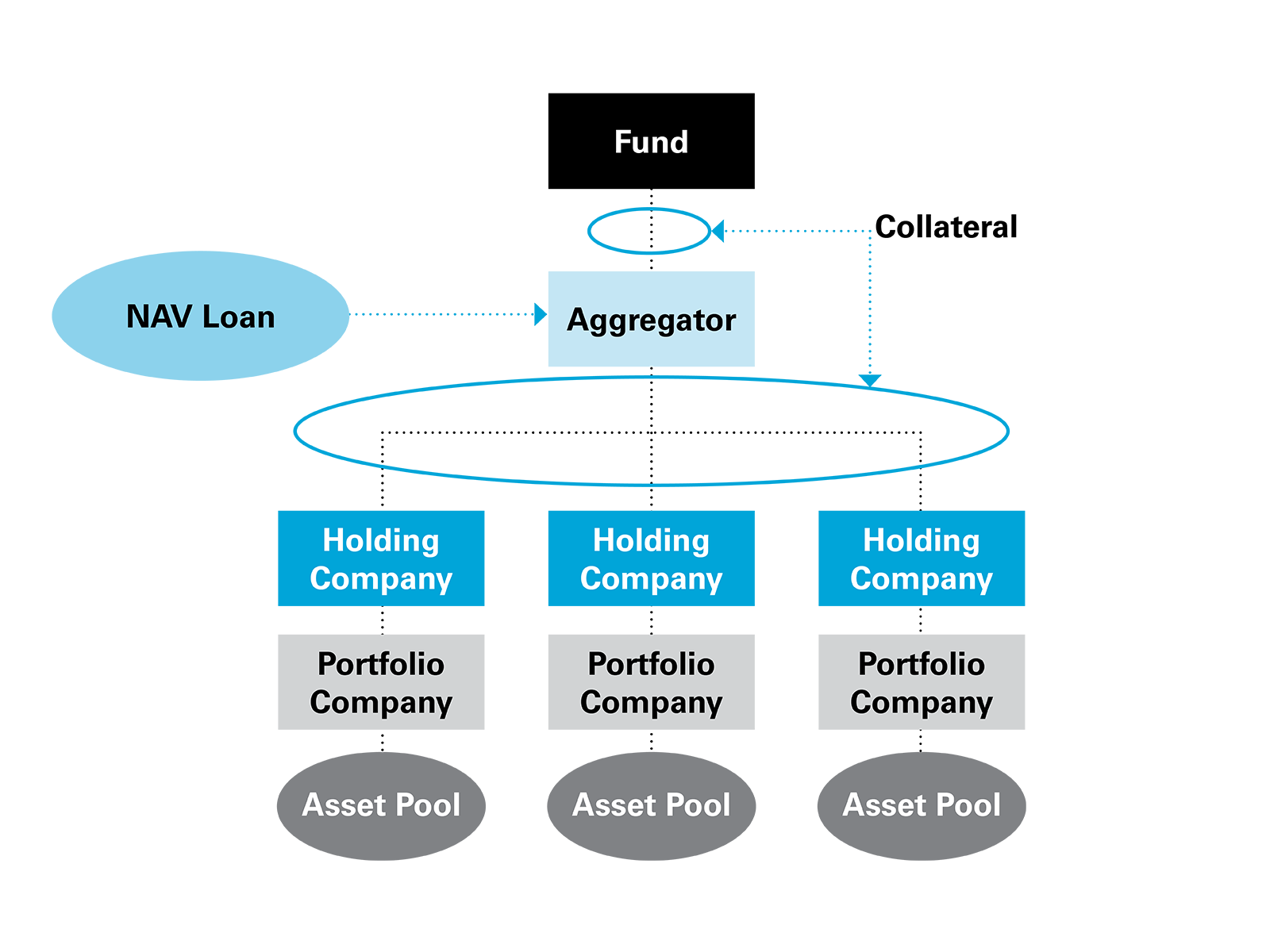

In terms of structuring, NAV loans for PE and infra funds typically provide for the borrower to be the fund itself (including any parallel investment vehicles and alternative investment vehicles) or an aggregator vehicle beneath the fund. In both cases, the NAV facility will be secured by a pledge of the equity interests directly held by the borrower in the holding companies through which the portfolio investments are held (see fig. 3) as well as any bank accounts of the NAV borrower into which proceeds from the portfolio will be paid. Where an aggregator is the borrower, the NAV facility may also be secured by a pledge of the equity of the aggregator borrower (see fig. 4).

Simple, no? Well, no.

As a result of the issues discussed above, as well as the fund's inherent interest in remaining in control of its portfolio and protecting the equity value for its investors, the nature of the equity interests pledged to a NAV lender and the degree to which enforcement of that pledge provides the lender with "step-in rights" to assume control of the portfolio investments and direct their disposition vary widely. The holding companies whose equity is pledged will most often be limited liability companies or LPs. The NAV lender and its counsel must thus identify how each of those entities is controlled, specifically:

- is it by a GP and, if so, can/would that GP also pledge its general partnership interest in the holding company;

- in the case of a limited liability company, is it member managed or manager managed and, if manager managed, would the lender be able to replace the manager upon enforcement; and

- is management delegated by its GP or member/manager to an investment manager and, if so, would the investment management agreement permit the lender to remove and replace the investment manager following enforcement?

The transfer restrictions and change of control issues discussed above may often be avoided by pledging only the economic interest of the underlying portfolio and leaving the fund in control as GP or manager of the pledged entities. While this solves one set of problems, though, it creates another – in an enforcement situation, the lender would be unable to transfer control of the underlying portfolio to a buyer. Any potential buyer of the pledged equity would be in much the same position as any other investor in the fund. That is, it would be reliant on the fund to manage and monetise the underlying investments and would only receive returns as and to the extent the fund chooses and is able to dispose of the portfolio assets at a profit. Although the fund would owe the same fiduciary duties to the buyer of the pledged equity as it owes to its investors, this set-up may nevertheless reduce both the universe of potential buyers for the pledged equity and the price a buyer would be willing to pay.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, we find transactions in which the NAV lenders require the fund to also pledge the general partnership/management interest in the pledged entities and/or to ensure that the relevant LPAs and other agreements permit a transferee to replace the GP and/or investment manager without cause following a foreclosure. The lender thus has the option to foreclose on both the general and LP interests where it finds it advantageous to do so, or it can foreclose only on the LP interest, leaving the buyer the option to replace the GP as and when practicable.

Inhabiting the middle of this continuum, we find an almost endless variety of "controlled sale" provisions. These provisions require that the fund take specified actions – often subject to a commercially reasonable standard – with a view to monetising sufficient assets in the portfolio to repay the NAV facility within a reasonably short (depending on the nature and liquidity of the portfolio assets) period of time.

For transactions in which the full equity interests in the portfolio holding companies, including both economic interests and control rights, have been pledged to the NAV lender, a controlled sale provision may take the form of an option by the NAV borrower to assume control of the disposition of portfolio assets so long as it complies with specified criteria and so long as no insolvency event of default occurs.

By contrast, other forms of controlled sale provisions may provide a deadline (e.g. three months from the occurrence of a default) for the NAV borrower to submit a plan reasonably acceptable to the NAV lender to monetise sufficient assets to repay the NAV facility, followed by a further period (which may vary in length depending on the natural time one would expect disposal of the relevant portfolio assets to require) for the NAV borrower to execute that plan.

Somewhere between these two extremes are provisions that provide for a timeline for the NAV borrower to monetise assets to repay the NAV facility but that permit the NAV lender to dictate the order in which assets in the portfolio will be disposed of.

Regardless of the form that controlled sale provisions may take, they universally provide that, unless an insolvency or other specified material event of default occurs or the NAV borrower fails to comply with the controlled sale requirements, the NAV lender is prohibited from exercising any control rights it may have to force disposition of portfolio assets and must wait for resolution of the controlled sale process.

Figure 3:

Figure 4:

Private equity and infrastructure preferred equity alternative

An alternative structure used for some PE and infrastructure NAV financings, which also has the benefit of avoiding the risk of triggering transfer restrictions, changes of control or regulatory consent requirements upon enforcement, uses a preferred LP interest to bifurcate the economic and ownership interests in the underlying portfolio. In this structure, the fund establishes a single aggregator SPV to hold the portfolio investments that will form the basis of the NAV facility. This SPV issues both a preferred LP (or membership, depending on the nature of the entity) interest as well as an ordinary LP or membership interest. The ordinary equity interest is issued to the fund in the usual manner. The preferred interest is issued to a second SPV, which is set up as an independent entity wholly owned by an orphan trust. This second SPV acts as the borrower for the NAV facility and pledges the preferred equity interest as collateral for the facility, together with its bank accounts (see fig. 5). This structure is much more commonly seen in Europe than in the United States.

The LPA or other governing document of the aggregator entity contains a waterfall such that any cash proceeds of the portfolio investments must first be paid to the preferred interest holder (that is, the NAV borrower) to the extent any amounts are owed under the NAV facility before any amounts can be distributed to the fund. Furthermore, any amendments to those governing documents that would negatively affect the NAV facility borrower (such as by changing the allocation of proceeds, permitting the incurrence of debt or liens, etc.) require the consent of the NAV borrower and, by extension, the NAV lender.

While this structure puts the NAV lenders further away from the portfolio investments, it has the advantage of offering collateral that can be more easily transferred without compromising value in the portfolio. Because the preferred equity interest held by the NAV borrower is not a voting interest and does not carry with it GP or other control rights (save for ordinary minority shareholder rights), any transfer of that interest in foreclosure would not result in a transfer of any underlying portfolio investment that might otherwise trigger transfer consent requirements, regulatory consents or a change of control.

As with the pledge of economic-only rights discussed with respect to the structures depicted in Figures 3 and 4 above, any purchaser in foreclosure acquires only an LP interest in the aggregator that holds the fund assets, and must wait until those assets are disposed of to receive a recovery. As a result, NAV lenders in these structures typically insist on the inclusion of controlled sale provisions that require the fund to develop an asset monetisation plan and use commercially reasonable efforts to dispose of portfolio investments as soon as reasonably practical in order to repay the NAV facility or, in the case of a preferred equity interest acquired in foreclosure, repay an amount equal to the principal plus accrued and unpaid interest on the NAV facility for which such preferred equity was pledged.

Figure 5:

Holdco back-levering/margin loans

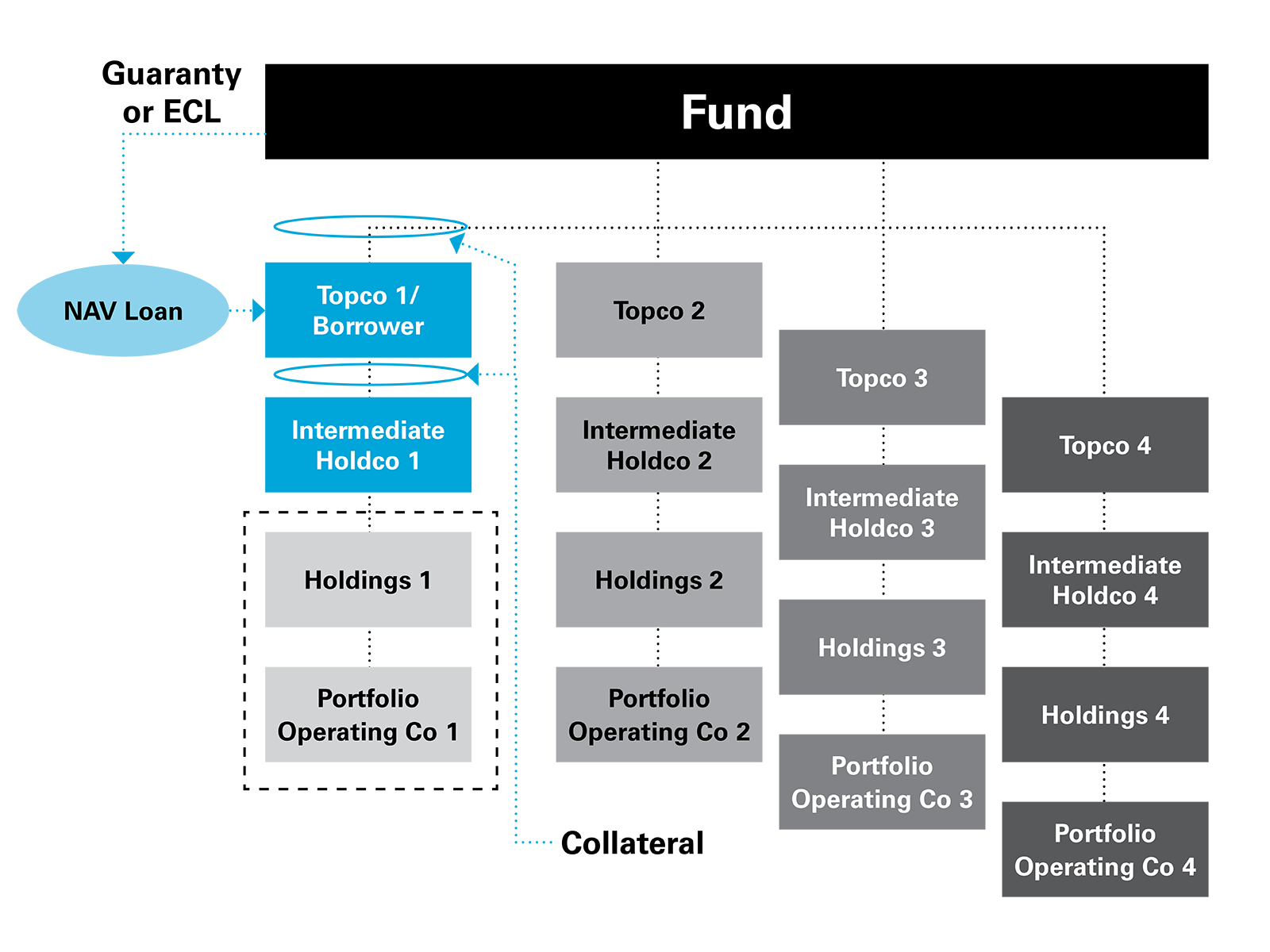

The final structure we would like to discuss is for "NAV-adjacent" holdco back-levering transactions. These are loans made to a holding company sitting atop a single portfolio investment. As we have discussed in prior editions of this book, these loans may feature a variety of NAV and margin loan characteristics. They are secured by a pledge of both the equity of the SPV borrower and its bank accounts as well as the equity interests of the next holding company down the corporate chain that is directly owned by the SPV borrower (see fig. 6). They also benefit from credit support from the fund in the form of a guaranty or equity commitment letter ("ECL"). It is this last feature that makes these loans "NAV-adjacent", because rather than relying solely on the equity value of the individual asset silo above which the SPV borrower sits, the loan benefits from an unsecured claim against the fund that relies on the full NAV of the entire fund portfolio. Typically, the same covenants that would appear in a portfolio NAV such as that see in Figure 3 – e.g. minimum NAV, fund asset coverage tests, NAV decline covenants and minimum liquidity requirements – will apply here as well pursuant to the fund guaranty or ECL covenants.

In terms of collateral, the diligence and considerations that apply to other forms of NAV financings are equally, if not more, important here. If the portfolio investment held by the SPV borrower is majority owned and controlled by the SPV borrower, the NAV lender and its counsel will engage in much the same diligence exercise as for a PE or infra portfolio, albeit limited to a single asset. This will include understanding the change of control provisions applicable to the portfolio company, any regulatory consents triggered by a change of control and any other transfer restrictions that might be tripped by an enforcement of the pledges. Discussions as to the extent of NAV lender step-in rights and potential negotiation of controlled sale provisions will also be equally applicable.

One important distinction that often applies to these loans is that, unlike in a typical PE or infra NAV financing, the portfolio company investment relevant to these financings will frequently be a minority interest. This feature has numerous other implications for the structure and terms of the financing – a topic for another chapter. With respect to the collateral for the NAV financing and the rights to be obtained on enforcement of the security, it will frequently mean that the transfer restrictions contained in the shareholders' agreements and other organisational documents of the portfolio company will somewhat constrain the NAV lender's potential enforcement actions, and understanding these limitations will be of critical importance to the NAV lender. As with secondaries interests, the transfer restrictions may be defined broadly to include "indirect" transfers and thus be triggered by the pledge itself as well as by any attempt to foreclose on the pledged equity. These restrictions may require consent of the portfolio company or some or all of its other equityholders in order for the SPV borrower to grant the requisite pledge.

Similarly, any proposed direct or indirect transfer of the portfolio company interest – whether by the SPV borrower or by the NAV lender via its security – will often be subject to rights of first refusal and tag-along provisions in favour of other equityholders in the portfolio company. As a holder of only a minority interest, the SPV borrower and its NAV lender generally will not benefit from drag-along provisions that would enable it to cause a sale of the entire portfolio company. Moreover, the NAV lender should be cognisant that the equity held by its borrower may itself be subject to drag-along rights in favour of other portfolio company equityholders, potentially resulting in a forced sale of the borrower's investment on terms or at a time that the NAV lender views as sub-optimal.

Figure 6:

In summary, the structure of the collateral package for a NAV or NAV-adjacent financing, as well as the degree to which the NAV lender will achieve control of its destiny on enforcement, will vary widely depending on the nature of the underlying assets, the terms of applicable agreements governing those assets and the negotiating position and relative interests of the parties. It is imperative that NAV lenders understand not only the legal regimes applicable to enforcement of their security but also the practical implications of doing so. Achieving an acceptable path to enforcement will require careful analysis of the law governing the proposed security as well as the network of contractual and/or regulatory considerations relevant to any attempt to obtain or transfer control of the NAV borrower's investment. Given the variety of fund structures, portfolio company holding structures and underlying assets, this analysis is a bespoke undertaking for each financing. Using the generic structure and terms outlined above as interchangeable building blocks rather than as "one-size-fits-all" mandates, however, will almost always enable the parties to devise a creative solution that balances the needs of the NAV lender and NAV borrower in a manner acceptable to both.

1 Please see our chapter in GLI – Fund Finance 2024 titled "NAVs meet margin loans: Single asset back-levering transactions and concentrated NAVs take centre stage".

The article was first published on GLI - Fund Finance 2025 and is available here.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2025 White & Case LLP

Figure 1 (PDF)

Figure 1 (PDF)

Figure 2 (PDF)

Figure 2 (PDF)

Figure 3 (PDF)

Figure 3 (PDF)

Figure 4 (PDF)

Figure 4 (PDF)

Figure 5 (PDF)

Figure 5 (PDF)

Figure 6 (PDF)

Figure 6 (PDF)