Corporate structuring under the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement – with a cautionary tale for Chinese-owned investors

7 min read

Structuring an investment to ensure adequate treaty protection is critical, particularly where the investment is being made in a jurisdiction prone to sovereign risk. If a holding company is created to ensure recourse under an investment treaty in the event of adverse government action, that company must meet the jurisdictional requirements in the applicable investment treaty.

This note looks at the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement – specifically, the treaty's definition of an "investor" which must be read alongside the often overlooked "denial of benefits" provision featured toward the back end of the treaty. In the current geo-political climate, Chinese-owned investors should understand the additional risk that another State's breakdown of diplomatic relations with China may have on any investment.

The ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement

The State parties to the ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement (2009) (hereafter, "ASEAN Agreement") are the Governments of Brunei Darussalam, the Kingdom of Cambodia, the Republic of Indonesia, the Lao People's Democratic Republic, Malaysia, the Union of Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, the Kingdom of Thailand, and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The treaty contains standard investment protections and provides the ability for an investor to submit claims against a State party to ICSID or under UNCITRAL to a regional centre for arbitration in ASEAN.

Investor

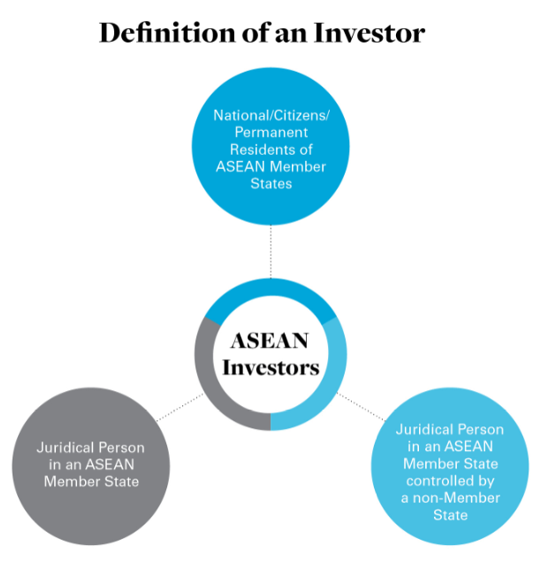

To access the benefit of the ASEAN Agreement, the investment in the applicable host State must be made through an entity that qualifies as an "investor" of the host State.

Article 4 provides:

- "investor" means "a natural person of a Member State or a juridical person of a Member State that is making, or has made an investment in the territory of any other Member State"; and

- "juridical person" means "any legal entity duly constituted or otherwise organized under the applicable law of a Member State…"

To qualify as an investor, the language used in more modern treaties typically requires more than simply formal incorporation and or registration of a holding company in a country. Often, to qualify for protection, the company that is incorporated or registered in a country is required to conduct substantive business operations in that country. The rationale for this additional requirement is to discourage the creation of shell companies and ensure there is a genuine connection to the host State, for a company to qualify for protection.

For example, under the Netherlands-Philippines BIT, there is a requirement that the investor is "actually doing business" in the host State and there has "a place of effective management".1 Therefore, to the extent that (for example) a Dutch SPV is interposed into a corporate structure to acquire an investment in the Philippines, the Dutch SPV must actually do business, and have a place of effective management, in the Philippines. This requires more than simply a registered address, and seeks to ensure the company has a genuine commercial connection there.

By contrast, in the ASEAN Agreement, there is no "effective management" or "actually doing business" requirement in the definition of "investor" or "juridical person".

However, there is a denial of benefits clause which should not be ignored.

Denial of benefits

A denial of benefits clause permits a contracting state to deny the protections of the treaty to certain categories of investors whom the treaty did not intend to protect. For example, an ASEAN Member State may deny the benefits of the treaty to an investor of another ASEAN Member State in the circumstances described below.

Article 19(1) of ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement

Article 19(1) provides. in part:

A Member State may deny the benefits of this Agreement to:

(a) an investor of another Member State that is a juridical person of such other Member State and to investments of such investor if an investor of a non-Member State owns or controls the juridical person and the juridical person has no substantive business operations in the territory of such other Member State;

[ ... ]

(c) an investor of another Member State that is a juridical person of such other Member State and to an investment of such investor if investors of a non-Member State own or control the juridical person, and the denying Member State does not maintain diplomatic relations with the non-Member State.

Non-member State owned or controlled, and no substantive business operations

Under Article 19(1)(a), an ASEAN Member State may deny the benefits of the ASEAN Agreement to an investor (e.g. a Singaporean SPV) if the investor of a non-Member State (e.g. a Chinese parent company) owns or controls the Singaporean SPV and the Singaporean SPV has no substantive business operations in Singapore.

Article 19(3) gives some guidance to the meaning of "owned" and "controlled".

- A juridical person is owned by an investor in accordance with the laws, regulations and national policies of each Member State. This is a question of the law of the applicable Member State.

- A juridical person is controlled by an investor if the investor has the power to name a majority of its directors or otherwise legally direct its actions. This is a question of fact.

In the example above, the relevant factual enquiry is whether the Chinese parent has the power to legally direct the actions of the Singaporean SPV. If it does, the question will be does the Singaporean SPV have substantive business operations in Singapore? The phrase "substantive business operations" is construed having in mind the purpose of the denial of benefits clause, which is to exclude shell companies from improperly obtaining treaty protection. Typically, it is the materiality (not the magnitude) of the company's business activity that is decisive. Tribunals have found the following factors relevant in determining the existence of "substantive business operations":

- payment of different types of taxes;

- leased office space;

- maintenance of bank accounts;

- payment of salaries; and

- location of Board meetings and where directors reside.

In addition, a law firm's report showing the investor's main activity has been held to be good evidence.

Non-member State owned or controlled, and breakdown of diplomatic relations

Under Article 19(1)(c), an ASEAN Member State may deny benefits to investors owned or controlled by a non-Member State in circumstances where the ASEAN Member State does not have diplomatic relations with that non-Member State. Such an article may be triggered by a State to deny protection to another State's investors "with which diplomatic relations have been discontinued or that is the object of sanctions".2 A provision of this nature, giving a State the right to deny treaty benefits on the basis of diplomatic or economic relations, is found in (it is estimated) less than 4% of all international investment agreements worldwide.

Unsurprisingly, there are no known cases of a State exercising its right under clause 19.1(c). Indeed, before 2023, there was no instance where a State had triggered a denial on the basis that it does not maintain diplomatic relations with another State.

However, in 2023, in the context of the war against Ukraine, some State Parties to the Energy Charter Treaty, which contains a similar denial of benefit provision in Article 17(2)(a), denied Russia and its investors the ability to benefit from the provisions of that treaty.3

And, in the current geopolitical climate, including the rising tensions in the South China Sea, Chinese-owned or controlled investors should, similarly, be aware of this underlying risk in the ASEAN Agreement. Put simply, the ability exists for an ASEAN Member State (such as the Philippines) to deny the benefits of the ASEAN Agreement to an investor owned or controlled by a Chinese parent, if there is a breakdown in relations with China and/or if that ASEAN Member State purports to sanction China and its investors.

Were the right to be exercised (and it must be actively exercised by a State), Article 19 is silent on the manner in which the State would exercise the right. In reality, a State is unlikely to become aware of a scenario in which it might wish to invoke the denial of benefits right until it is served with a notice of dispute or a request for arbitration. But certainly any denial would have to be timely.

The author acknowledges Samara Cassar and Klyde Yang for their assistance in the preparation of this publication.

1 Article 1(b)(ii).

2 Yas Banifatemi, "Taking into account control under denial of benefits clauses", Jurisdiction in Investment Treaty Arbitration (2018), 227.

3 See, Letter from Minister for Foreign Affairs of Ukraine (August 2022). Accessible here. Letter from Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action, Berlin (15 March 2023). Accessible here. UK Denial of Benefits Notification (29 September 2023). Accessible here.

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2024 White & Case LLP