Voluntary carbon markets: will carbon credits soon become a crucial way to decarbonise?

4 min read

Purchasing carbon credits was once seen as a way for companies to sidestep genuine emissions reduction in their decarbonisation efforts. But that is changing as these products, and the way they are used, face growing scrutiny. The increasingly competitive voluntary carbon credit market could play an important role in net zero goals for companies that cannot meet their targets through emissions reductions alone. Additionally, when these companies buy carbon credits from projects that reduce or remove emissions, the funds can be used to help support the transition to clean energy globally.

What is carbon trading?

Voluntary carbon credit markets work by treating carbon dioxide and certain other greenhouse gases as a tradeable commodity. Every tonne reduced or removed affects atmospheric levels globally — regardless of geographic location. This means organisations can offset their emissions by buying carbon credits generated anywhere in the world.

Methods of reducing carbon dioxide levels include nature-based solutions, such as reforestation and soil management; technologies such as direct air capture, which extracts carbon dioxide from the atmosphere; and enhanced rock weathering, which accelerates the process by which rocks absorb carbon.

Removal technologies are often referred to as carbon capture and storage (CCS) or carbon capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS). CCS makes permanent storage of carbon possible, CCUS reuses it in industrial processes.

Some CCUS methodologies allow a company to generate credits if, after removing and storing the carbon, it uses it in a subsequent project that converts it into, for example, plastic, concrete or biofuels. "But that's a small piece of the market," says Seth Kerschner, a partner in law firm White & Case's New York office. "Most of the projects we see are long-term storage of the carbon."

Better monitoring, standards and understanding

Voluntary carbon markets have undergone a major shift in recent years. There was once widespread scepticism about whether some credits genuinely contributed to emissions reduction, but greenwashing is now less of a concern.

This is partly because it is easier to spot. Digital technologies such as satellite imaging and remote sensing provide real-time, on-the-ground data that can verify claims about the sequestering (capturing and storing) of carbon dioxide.

With the help of ratings agencies, voluntary markets standards setters and initiatives such as the Integrity Council for Voluntary Carbon Markets, clarity is emerging on what qualify as high-quality credits. These credits must:

- Be evaluated using robust methodologies

- Not risk impermanence (such as forests that might later be felled)

- Have 'additionality', which means that the carbon reduction would not have occurred without the revenue from the sale of the credits

The market itself is also having an influence. Large-scale buyers of credits are demanding higher-quality credits and are avoiding those that use unreliable methodologies. And some sellers will either withhold from potential buyers any credits that lack a credible carbon reduction strategy, or charge a premium for better credits.

We're seeing the price of carbon credits begin to reflect the quality

"It's moving the market in the right direction," says Ingrid York, a White & Case partner who practises in the firm's Capital Markets group in London. CCS credits, she explains trade significantly higher because their permanence (meaning that the carbon removed is securely stored for several centuries) is certain. "We're seeing the price begin to reflect the quality."

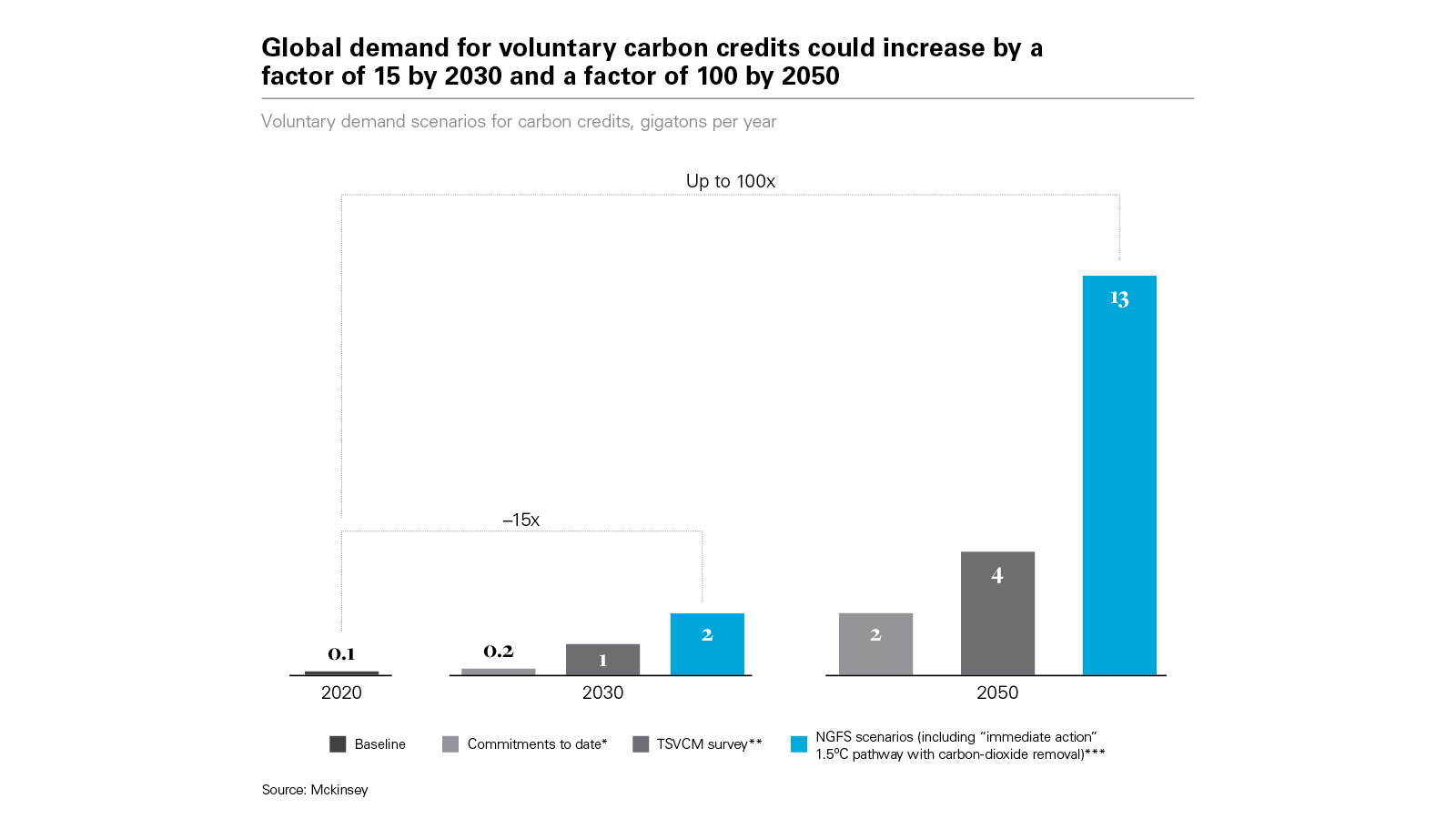

NGFS: Network for Greening the Financial System. These amounts reflect demand based on carbon-dioxide removal and sequestration requirements under the NGFS's 1.5°C and 2.0°C scenarios.

Companies are also under growing pressure to use voluntary carbon markets responsibly. For example, the UN-backed Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) stipulates that credits cannot be counted towards SBTi goals, which require measurable reductions within a company's own operations and across its value chain The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative, meanwhile, provides guidance on how companies should use credits to make claims about their emissions reductions.

Carbon markets are here to stay

The prospect of a large bill down the line – whether in the form of fines or having to pay a far higher price for carbon credits – gives companies one incentive to invest more in cutting their operational emissions. Since they will eventually need to meet regulatory emissions-reduction requirements, postponing investments could leave them racing to buy credits later — when prices could be significantly higher.

Disclosure requirements will also play a role in pushing companies to reduce their operational emissions. "New regulations require companies to disclose their offset purchases, making their approach with respect to offsetting versus emissions reduction much more public," says Taylor Pullins, a partner in the Global Environmental Practice in White & Case's Houston office. "This could lead to additional reputational risk for disclosing companies and demands for increased emissions reduction efforts."

As a result, carbon credits are increasingly being treated as part of a broader decarbonisation strategy and are used only after operational emissions-reduction efforts have been exhausted.

"The carbon markets are here to stay," says York. "They're more sophisticated, with higher-quality products, and are clearly among the suitable tools in the decarbonisation toolkit."

Looking ahead, Kerschner sees the next phase as one in which companies will seek to use carbon removals to offset past emissions. "They'll look backward," he says. "And the markets will need to support that, because it's even harder to do."

White & Case means the international legal practice comprising White & Case LLP, a New York State registered limited liability partnership, White & Case LLP, a limited liability partnership incorporated under English law and all other affiliated partnerships, companies and entities.

This article is prepared for the general information of interested persons. It is not, and does not attempt to be, comprehensive in nature. Due to the general nature of its content, it should not be regarded as legal advice.

© 2024 White & Case LLP

Global demand for voluntary carbon credits could increase by a factor of 15 by 2030 and a factor of 100 by 2050

Global demand for voluntary carbon credits could increase by a factor of 15 by 2030 and a factor of 100 by 2050